The Oxford University Hospitals Foundation Trust Pilot

The Oxford University Hospitals Foundation Trust Pilot

By Dr Christopher Speers, Sport and Exercise Medicine Consultant Oxford University Hospitals Foundation Trust

Physical inactivity is the fourth leading cause of death worldwide1 and it contributes significantly to the worldwide burden of non-communicable disease2, 3. Hospitals, historically, have been dominated by a culture of rest4. Promoting rest contradicts the evidence which clearly demonstrates that disease outcomes are better for moving more and that post hospital syndrome, or hospital deconditioning, leads to increased risk and adverse outcomes5, 6. Furthermore, there is a significant evidence-base demonstrating the potential for physical activity to improve management and treatment outcomes for a wide range of long-term health conditions, including arthritis7.

Healthcare provides a unique point of access to a section of the population who are likely to gain the most from only small improvements in increasing their physical activity. Therefore hospital admission is a key opportunity to influence patients to change behaviour for the better. This preventative approach to healthcare is a key objective of the NHS 10 year plan8.

‘Moving Healthcare Professionals’ forms part of Public Health England’s (PHE) ‘Everybody Active Every Day’ strategy9, and aims to engage professional networks to support understanding and awareness of, and greater engagement in, physical activity among the wider public.

In 2017, PHE and Sport England invited expressions of interest from applicable NHS Trusts (i.e. the Trust employs a Sports and Exercise Medicine (SEM) consultant to deliver a SEM pilot in secondary care. We were successful and were commissioned to deliver an SEM pilot that focused on the integration of physical activity into care pathways within secondary care.

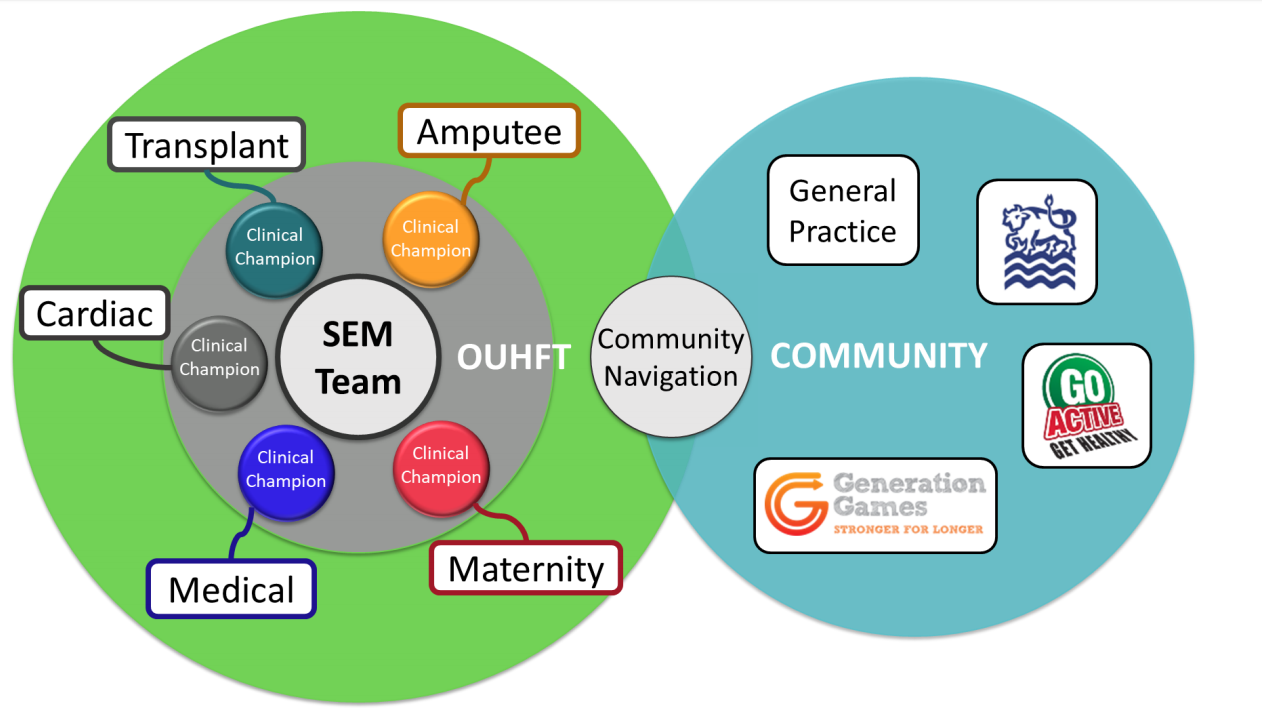

The primary aim of the SEM pilot was to explore the potential for multi-disciplinary SEM teams in secondary care to contribute to patient outcomes through targeted and tailored support to integrate physical activity into the care plans of in-patients prior to discharge. We developed physical activity interventions across five different clinical pathways involving multi-morbidity and frailty (figure 1). Each intervention was designed using the COM-B model and Behaviour Change Wheel10. A clinical champion was employed within each pathway to develop and deliver the interventions, provide leadership and training to other staff within that clinical setting.

A range of different interventions were used to improve the levels of physical activity in patients, but underpinning our approach was an ambition to target healthcare professionals and change their behaviour to improving the frequency and quality of conversations between staff and patients about physical activity. Tools to do this included integrating the Exercise Vital Sign11, 12 into electronic patient records, staff training in motivational interviewing, exercise classes, as well as bed-, chair-based, and standing-exercise programs matched to functional ability of patients. A community navigator was available to help patients and staff members find community-based exercise teams and classes during the discharge process to ensure integrated care.

External independent evaluation was undertaken by the National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine in Sheffield; early reports have shown that this approach is highly valued and acceptable to patients and staff within the NHS. We have learnt a huge amount about integrating physical activity into secondary care systems throughout the pilot, and are going to publish our findings, learning and experience in the form of an ‘Active Hospital Toolkit’ later in 2019. This will be accessible through the Moving Medicine website.

External independent evaluation was undertaken by the National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine in Sheffield; early reports have shown that this approach is highly valued and acceptable to patients and staff within the NHS. We have learnt a huge amount about integrating physical activity into secondary care systems throughout the pilot, and are going to publish our findings, learning and experience in the form of an ‘Active Hospital Toolkit’ later in 2019. This will be accessible through the Moving Medicine website.

References:

- Kohl HW, Craig CL, Lambert EV, Inoue S, Alkandari JR, Leetongin G, Kahlmeier S; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. The pandemic of physical inactivity: global action for public health. Lancet. 2012 Jul 21;380(9838):294-305.

- Lee IM, Shiroma EJ, Lobelop F, Puska P, Blair SN, Katzmarzyk PT; Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. Effect of physical inactivity on major non-communicable diseases worldwide: an analysis of burden of disease and life expectancy. Lancet. 2012 Jul 21;380(9838):219-29.

- Blair SN. (2009) Physical inactivity: the biggest public health problem of the 21st century. British Journal of Sports Medicine; 43:1-2

- Brown CJ, Redden DT, Flood KL, Allman RM. The underrecognized epidemic of low mobility during hospitalization of older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc . 2009;57:1660–1665.

- HM Krumholz Post-hospital syndrome—an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:100-102.

- Wen CP, Wai JPM, Tsai MK, Yang YC, Cheng TYD, Lee M, et al. (2011) Minimum effort of physical activity for reduced mortality and extended life expectancy. The Lancet; 378:(9798): 1244-1253.

- Gleeson, M., Bishop, N. C., Stensel, D. J., Lindley, M. R., Mastana, S. S. & Nimmo, M. A. 2011. The anti-inflammatory effects of exercise: mechanisms and implications for the prevention and treatment of disease. Nature Reviews Immunology, 11,

- NHS England NHS Long Term Plan. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/ (accessed on 27.03.2019.

- Public Health England 2014. Everybody Active Everyday: National Physical Activity Framework. In: ENGLAND, P. H. (ed.). London: Public Health England.

- Michie, S., Atkins, L. & West, R. 2014. The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions, Great Britain, Silverback Publishing

- Sallis R, Franklin B, Joy L, et al. Strategies for promoting physical activity in clinical practice. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 2015;57:375–86.

- Coleman KJ, Ngor E, Reynolds K, et al. Initial Validation of an Exercise ‘Vital Sign’ in Electronic Medical Records. Med Sci Sport Exerc 2012;44:2071–6