Guest blog by Ms. Nuzhat Ali, National MSK Lead, Public Health England

Guest blog by Ms. Nuzhat Ali, National MSK Lead, Public Health England

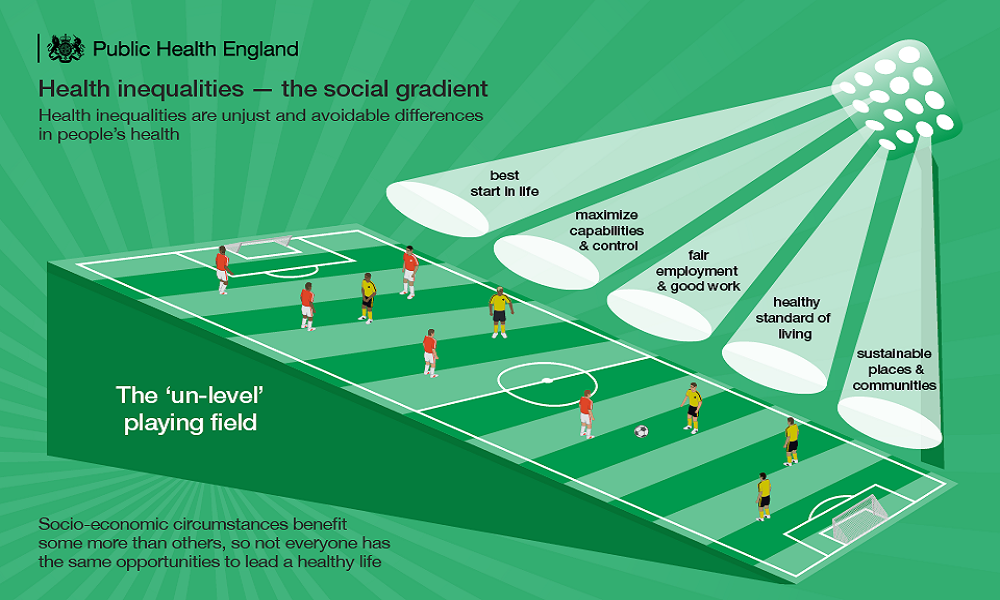

Health inequalities are avoidable, unjust differences in people’s health that are persistent and difficult to shift, until and unless we actively focus on them as a society and a whole system.

People living in the most deprived areas in England can expect to spend nearly 20 fewer years in good health compared with those in the least deprived areas. The trajectory and the scale of the inequity worry me for at least three reasons – it is:

- A societal injustice, one that has serious consequences for us all in many ways

- A factor in slowing down life expectancy and healthy life expectancy

- Increasing demand for health care which equates to increasing costs

Health is dependent on so much more than healthcare. Research from the Canadian Institute of Advanced Research, Health Canada, Population and Public Health Branch found that healthcare contributed no more than 25% to our health, and others like McGiniss et al found from their research that it is a 15% contribution. Our genes, lifestyle behaviours, environment, housing, socioeconomic and working conditions, and much more are all key determinants of our health. Surely this points to the need for us all to focus greater attention to these factors in meaningful ways.

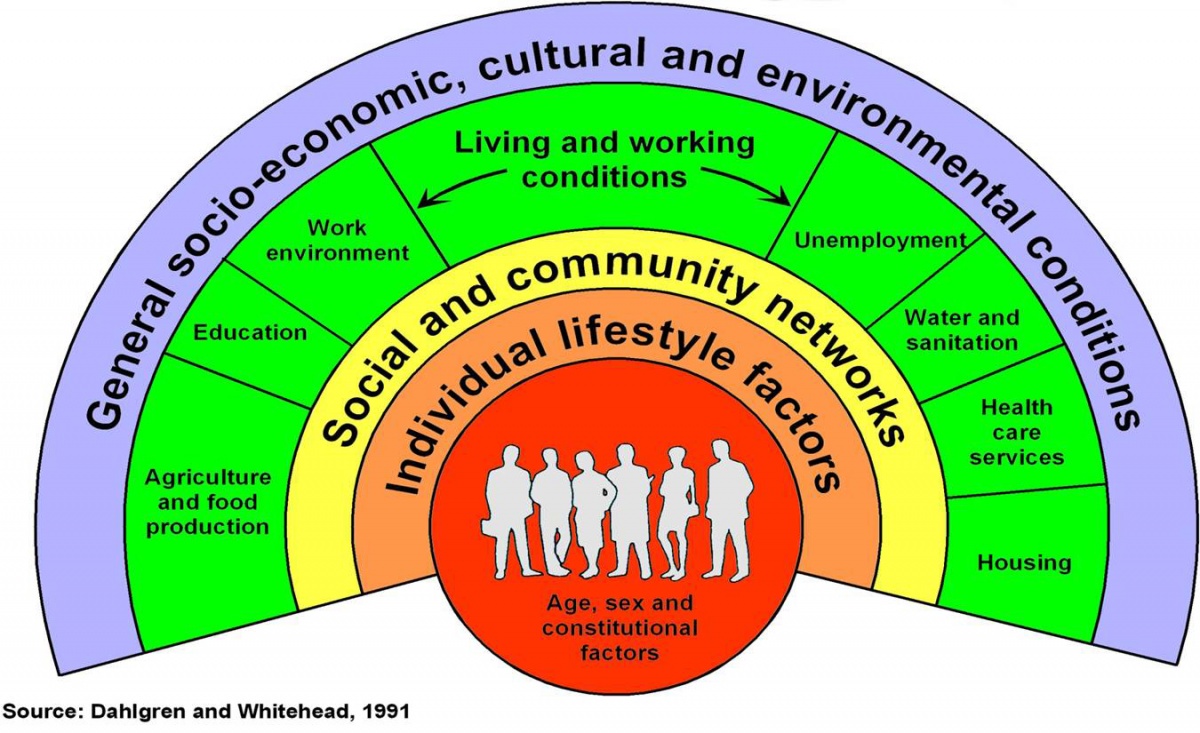

The Determinants of Health (Dahlgren and Whitehead, 1991)

The figure above shows the main determinants of health as layers of influence. At the centre of the model, individuals are endowed with non-modifiable factors that influence health potential, including age, sex and constitutional factors.

Surrounding the individuals are layers of influence that can be modified. The innermost layer represents the personal behaviour and way of life adopted, such as smoking habits and physical activity, with the potential to promote or damage health. Individuals interact with friends, relatives and the community, and are therefore affected by the social and community influences represented in the next layer. Mutual support within a community can sustain the health of its members in otherwise unfavourable conditions.

The wider influences on a person’s ability to maintain health include their living and working conditions, food supplies, and access to essential goods and services. Overall, there are the economic, cultural and environmental conditions prevalent in society as a whole, represented in the outermost layer.

What do we know about the relationship between musculoskeletal (MSK) health and inequality?

Gender differences:

An estimated 17.8 million people live with a MSK condition in the UK, which is around 28.9% of the total population. Of these, 7.7 million are men and 10 .1 million are women.

Socioeconomic differences:

People who live in the most deprived areas are much more likely to report arthritis or back pain than people in equivalent age groups who live in less deprived areas. 40% of men and 44% of women in the poorest households report chronic pain, compared to 24% of men and 30% of women in the richest households.

Among people aged 45–64, the prevalence of arthritis is more than double in the most deprived areas (21.5%) compared to the least deprived areas (10.6%). Further, people of working age (45–64 years) are almost twice as likely to report back pain (17.7%) as those from least deprived areas (9.1%).

Physical inactivity, obesity and comorbidity are all strongly associated with deprivation. People in the most deprived areas develop multi-morbidity 10–15 years earlier compared to those in the least deprived.

My top three humble suggestions on how we might tackle this wicked system problem:

- Balance the medical model of health with the social model of upstream efforts on wider determinants of health. This means working in partnership and collaboratively across sectors and with our community’s

- Focussed secondary prevention in primary care is the best way to get quick wins in narrowing health inequalities (King’s Fund)

- Provide targeted support to help people find and remain in good work

Public Health England (PHE)’s mission is to protect and improve the nation’s health and wellbeing, and reduce health inequalities. PHE have published a range of tools and resources to support professionals to tackle inequalities. PHE’s guidance – Reducing health inequalities: system, scale and sustainability – set out a revision of the DHSC’s Health Inequalities National Support.

For further information, you can visit PHE’s return on investment tool for MSK conditions, Health Matters and the recently published review on muscle and bone strength and balance.